Chris Roams

Travel, Adventures, and Photography

And Then Things Got Weird

January 08, 2012

Heading back south from Mono Lake I branched off from the main road down Owens Valley to explore one of the less-visited corners of Death Valley National Park. Until the park expansion in 1994 Saline Valley was just another swath of public land under the care of the Bureau of Land Management. Today it lies in the far northwest corner of the park, split from the Owens Valley to the north and west by the Inyo Range, shielded from Panamint Valley to the south by the Nelson Range and Darwin Plateau, and cut off from Death Valley to the east by a jumble of intermediate ranges and smaller high elevation valleys. Like most of these dead-end valleys the floor is the location of a salty lakebed although the purity of the salt in this particular lakebed was such that in 1911 another tram, similar to the one in operation at Cerro Gordo, was built 13 miles over the Inyo Range, gaining 7,400 feet of elevation in the process and losing 4,900 feet on the other side, so that the salt could be hauled out and sent to market. The tram is long since shut down and today the easiest way into this valley is via a long road that splits off from pavement east of the town of Big Pine in Owens Valley and rejoins pavement 75 miles to the south on the plateau between Owens Lake and Panamint Springs. In between is every conceivable road surface including washboard dirt, loose gravel, deep sand, jumbled rocks, deep ruts, and a section marked on the map at least as “paved” (technically accurate, it was probably paved… once… in the 1960′s).

For most of the road’s length through Saline Valley itself it hugs the western edge of the valley and defines the border between the National Park to the east and Inyo National Forest to the west. A dune field sits in the northern end of the valley and a road branches off across the valley and into the national park just to the north. The official Death Valley National Park map shows this as a “high clearance” road across empty desert, eventually turning into a 4wd road with the stern warning that “Road conditions require experienced 4-wheel drivers”. In reality for even the “high clearance” segment “Road” is a bit of a misnomer, for the first 3 miles a more accurate description would be “the strip of sand that people drive on”. The first sign that something is hiding out along this road comes at the end of the sand in the form of a tall metal post sporting various old car parts and a metal bats. A few miles beyond is a grove of palm trees, shockingly out of place in this valley where there are not other plants more than 3 feet high.

The anomalous palm trees mark the location of a series of hot springs in the northeastern corner of the valley, 38 miles from the nearest paved road, the ultimate boondocking site back before this area was added to the national park. Back in the 60′s the regulars who camped here planted the palms and began building infrastructure around the springs. A stone patio now fills the area inside the palm grove and is interspersed with in-ground concrete tubs. Water from the hot spring’s source which lies on a small rise above the grove is fed by gravity down through pipes to circulate through the soaking tubs below. Another nearby cold spring has also been piped in to allow for a shower and a sink with hot and cold running water. A small grassy lawn sits at the edge of the grove, irrigated by the runoff from the soaking tubs and sprinklers connected to the plumbing from the cold spring. The entire system is off the grid, powered only by the geothermal heating of the water and the siphoning powers of gravity.

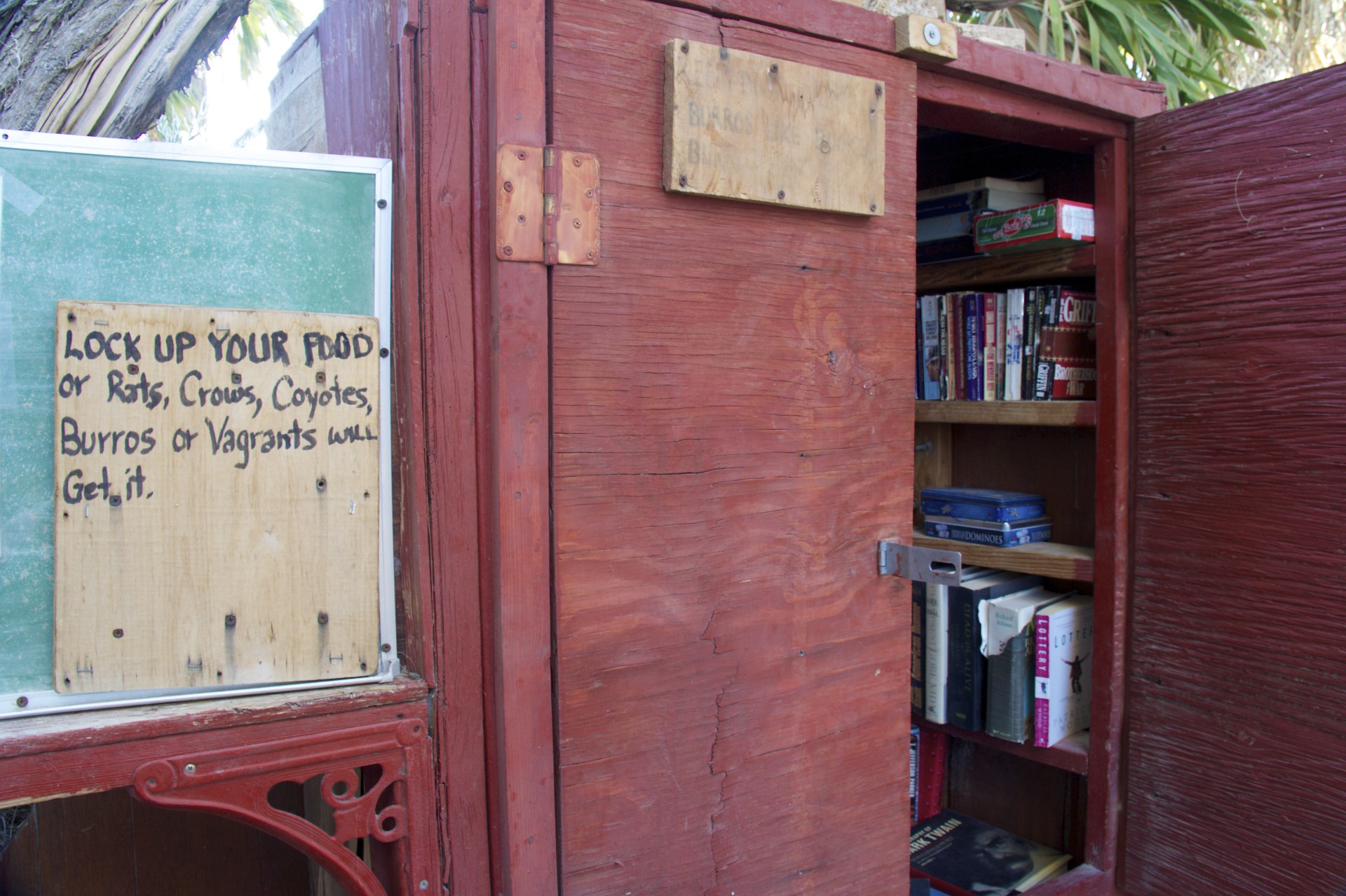

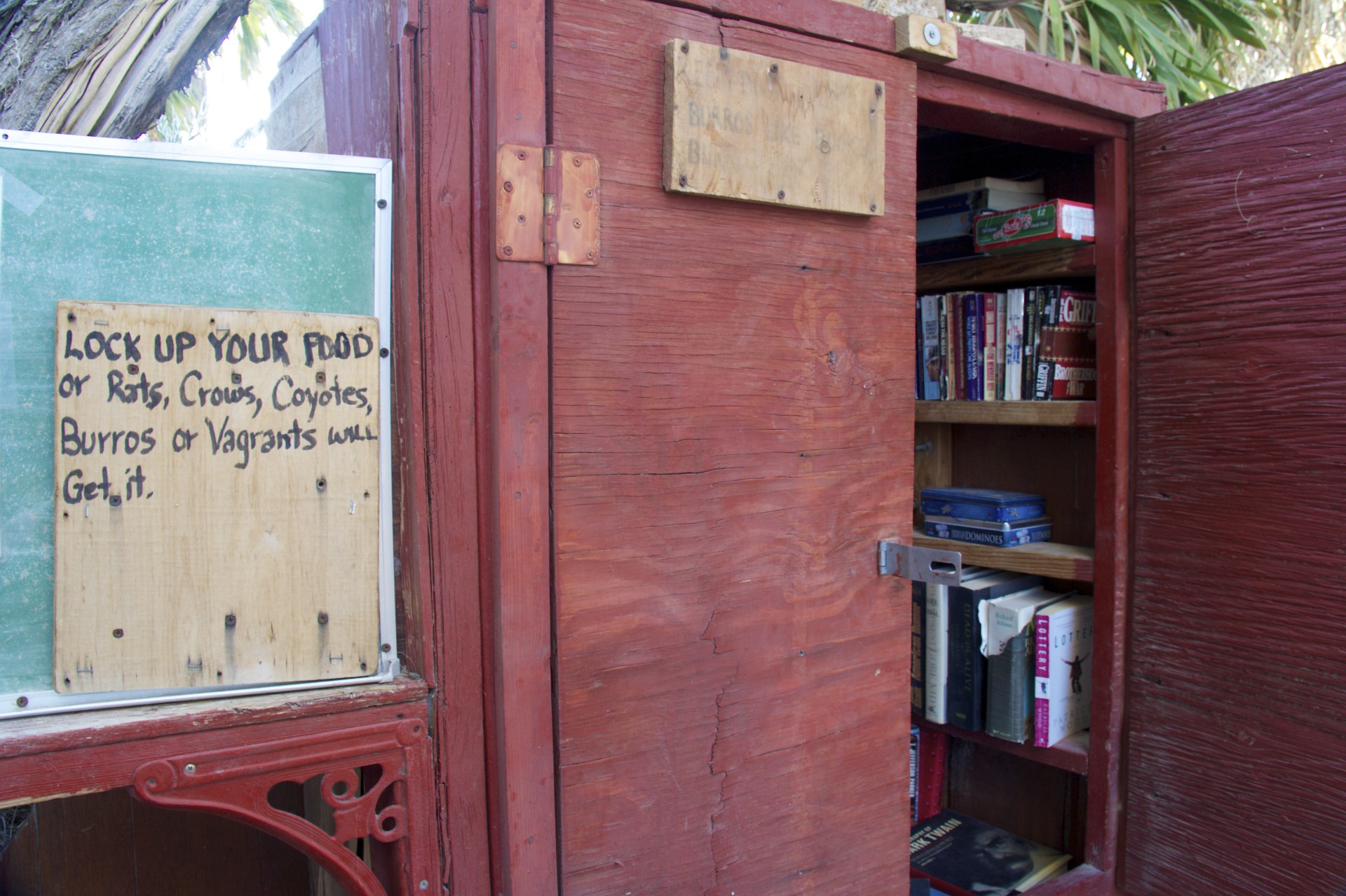

Although completely outdoors the grove has the feeling of a comfortable living room. The main grove is nearly surrounded by either a low stone wall or enough brush to provide the effect of being in an enclosed room with only 3 paths left open through the “walls” to get in and out. A military style camouflage net is strung between the palms over the largest of the soaking tubs to provide some shade and the rest of the enclosed patio contains a fire pit, benches, and picnic tables. One “wall” of this room hosts the aforementioned sink for cleaning up dirty dishes and an enclosed bookshelf where past travelers have contributed to a sizable library of books and board games. Out back is a small toolshed containing implements for maintaining the lawn and the brushy walls of this outdoor room. The entirety of the place is decorated with various knickknacks that have found their way here, from the skeletons of long deceased desert animals decorating the fire pit to the wire and glass baubles decorating the windows of the outhouses. Semi-serious hand-lettered signs (“LOCK UP YOUR FOOD or Rats, Crows, Coyotes, Burros, or Vagrants will get it.”) are interspersed with signs that appear to have been liberated from more serious locales and placed here for the irony (“CONSERVE WATER, REPORT ALL LEAKAGE TO PUBLIC WORKS OFFICE”). More recent official park service signs have sprouted up to bridge the gap between the seriously ironic signs and ironically serious signs with a dose of seriously serious, mandating the use of leashes for dogs and waterproof diapers for infants while prohibiting fireworks and the playing of drums after 10pm (apparently this is a problem here).

It’s almost a shame that the National Park Service has control of this place. The free-spirited philosophy that created this remote outpost on a desolate patch of public land seems entirely incompatible with a government agency that tends to treat anything that falls under their control as either a museum exhibit to be fenced off and labelled with interpretive signs or a wilderness to be kept devoid of man-made alterations. This corner of the park is already designated as wilderness which precludes roads (even the dirt kind) and leaving any permanent man-made constructions (concrete hot tubs included) although when the wilderness area was designated a tiny corridor was left for the existing road and construction at the springs to allow them to remain as-is for now. What has been built around the springs is neither suitable to be turned into a fenced off exhibit with a paved road and a parking but it shouldn’t be turned back into a barren steaming hole in the desert either: What has been built here is a testament to the creativity of the “desert rats”, the oddballs who come out to these remote places and choose to call them home, and deserves to be protected as a living place to be experienced first-hand by anyone resilient enough to make the trek. The community at the springs was very much alive right up until it came under the control of the park service but when control of the land changed hands the National Park camping limits came into effect forcing many of the regulars who helped build this place to leave or face the wrath of the rangers (much like the Timbisha Shoshone in Death Valley or the Havasupai tribe in the Grand Canyon who were informed that they would have to vacate their homes when their lands were added to the national park system). The park service does not provide for any maintenance of the springs and they are not even labelled on the park map. Only one of the “old-timers” who called this place home before the park came remains full-time as the NPS designated campground host, living in an ancient trailer on the hill alongside the spring and maintaining the spring with volunteer labor.

Only a few steps away from the hot spring and one is back out in the open desert. Wild burros wander the area, no doubt staying close to the springs both for the reliable water and to browse on the plant life that accompanies it. A rudimentary dirt airstrip lies a few hundred yards away for airborne visitors but the valley is more frequently visited by another type of aviator. The entirety of the national park as well as much of the land south and west of it lies under airspace controlled by the military and the Navy’s research and development facility at China Lake lies just to the south. Jets practice low level maneuvers here, dropping into the valleys below the ridges, the sound of the engines bouncing off the mountains and making it nearly impossible to identify the source.

The road out of the valley to the south winds its way across the valley floor, the washboard surface only interrupted briefly by sections of deep sand or rockslide debris, before twisting up a rocky, rutted pass in the Nelson Range to 6,200 feet, offering a view of the Panamint Valley to the south. Despite the proximity to Panamint Valley and it’s paved road to the south the direct line of descent town 2,500 vertical feet of canyon to the valley floor is just too steep and the road instead turns to the west where it crosses high elevation flat absolutely covered with joshua trees before rejoining the paved road at the park’s western boundary over 50 miles from the hot springs. Along the way a few other roads branch off leading to even more remote corners of the park but those will have to wait for another time. It’s back to Las Vegas for now, storage for the bike and a flight back to the east coast for me. This trip has come to an end for now.

For most of the road’s length through Saline Valley itself it hugs the western edge of the valley and defines the border between the National Park to the east and Inyo National Forest to the west. A dune field sits in the northern end of the valley and a road branches off across the valley and into the national park just to the north. The official Death Valley National Park map shows this as a “high clearance” road across empty desert, eventually turning into a 4wd road with the stern warning that “Road conditions require experienced 4-wheel drivers”. In reality for even the “high clearance” segment “Road” is a bit of a misnomer, for the first 3 miles a more accurate description would be “the strip of sand that people drive on”. The first sign that something is hiding out along this road comes at the end of the sand in the form of a tall metal post sporting various old car parts and a metal bats. A few miles beyond is a grove of palm trees, shockingly out of place in this valley where there are not other plants more than 3 feet high.

The anomalous palm trees mark the location of a series of hot springs in the northeastern corner of the valley, 38 miles from the nearest paved road, the ultimate boondocking site back before this area was added to the national park. Back in the 60′s the regulars who camped here planted the palms and began building infrastructure around the springs. A stone patio now fills the area inside the palm grove and is interspersed with in-ground concrete tubs. Water from the hot spring’s source which lies on a small rise above the grove is fed by gravity down through pipes to circulate through the soaking tubs below. Another nearby cold spring has also been piped in to allow for a shower and a sink with hot and cold running water. A small grassy lawn sits at the edge of the grove, irrigated by the runoff from the soaking tubs and sprinklers connected to the plumbing from the cold spring. The entire system is off the grid, powered only by the geothermal heating of the water and the siphoning powers of gravity.

Although completely outdoors the grove has the feeling of a comfortable living room. The main grove is nearly surrounded by either a low stone wall or enough brush to provide the effect of being in an enclosed room with only 3 paths left open through the “walls” to get in and out. A military style camouflage net is strung between the palms over the largest of the soaking tubs to provide some shade and the rest of the enclosed patio contains a fire pit, benches, and picnic tables. One “wall” of this room hosts the aforementioned sink for cleaning up dirty dishes and an enclosed bookshelf where past travelers have contributed to a sizable library of books and board games. Out back is a small toolshed containing implements for maintaining the lawn and the brushy walls of this outdoor room. The entirety of the place is decorated with various knickknacks that have found their way here, from the skeletons of long deceased desert animals decorating the fire pit to the wire and glass baubles decorating the windows of the outhouses. Semi-serious hand-lettered signs (“LOCK UP YOUR FOOD or Rats, Crows, Coyotes, Burros, or Vagrants will get it.”) are interspersed with signs that appear to have been liberated from more serious locales and placed here for the irony (“CONSERVE WATER, REPORT ALL LEAKAGE TO PUBLIC WORKS OFFICE”). More recent official park service signs have sprouted up to bridge the gap between the seriously ironic signs and ironically serious signs with a dose of seriously serious, mandating the use of leashes for dogs and waterproof diapers for infants while prohibiting fireworks and the playing of drums after 10pm (apparently this is a problem here).

It’s almost a shame that the National Park Service has control of this place. The free-spirited philosophy that created this remote outpost on a desolate patch of public land seems entirely incompatible with a government agency that tends to treat anything that falls under their control as either a museum exhibit to be fenced off and labelled with interpretive signs or a wilderness to be kept devoid of man-made alterations. This corner of the park is already designated as wilderness which precludes roads (even the dirt kind) and leaving any permanent man-made constructions (concrete hot tubs included) although when the wilderness area was designated a tiny corridor was left for the existing road and construction at the springs to allow them to remain as-is for now. What has been built around the springs is neither suitable to be turned into a fenced off exhibit with a paved road and a parking but it shouldn’t be turned back into a barren steaming hole in the desert either: What has been built here is a testament to the creativity of the “desert rats”, the oddballs who come out to these remote places and choose to call them home, and deserves to be protected as a living place to be experienced first-hand by anyone resilient enough to make the trek. The community at the springs was very much alive right up until it came under the control of the park service but when control of the land changed hands the National Park camping limits came into effect forcing many of the regulars who helped build this place to leave or face the wrath of the rangers (much like the Timbisha Shoshone in Death Valley or the Havasupai tribe in the Grand Canyon who were informed that they would have to vacate their homes when their lands were added to the national park system). The park service does not provide for any maintenance of the springs and they are not even labelled on the park map. Only one of the “old-timers” who called this place home before the park came remains full-time as the NPS designated campground host, living in an ancient trailer on the hill alongside the spring and maintaining the spring with volunteer labor.

Only a few steps away from the hot spring and one is back out in the open desert. Wild burros wander the area, no doubt staying close to the springs both for the reliable water and to browse on the plant life that accompanies it. A rudimentary dirt airstrip lies a few hundred yards away for airborne visitors but the valley is more frequently visited by another type of aviator. The entirety of the national park as well as much of the land south and west of it lies under airspace controlled by the military and the Navy’s research and development facility at China Lake lies just to the south. Jets practice low level maneuvers here, dropping into the valleys below the ridges, the sound of the engines bouncing off the mountains and making it nearly impossible to identify the source.

The road out of the valley to the south winds its way across the valley floor, the washboard surface only interrupted briefly by sections of deep sand or rockslide debris, before twisting up a rocky, rutted pass in the Nelson Range to 6,200 feet, offering a view of the Panamint Valley to the south. Despite the proximity to Panamint Valley and it’s paved road to the south the direct line of descent town 2,500 vertical feet of canyon to the valley floor is just too steep and the road instead turns to the west where it crosses high elevation flat absolutely covered with joshua trees before rejoining the paved road at the park’s western boundary over 50 miles from the hot springs. Along the way a few other roads branch off leading to even more remote corners of the park but those will have to wait for another time. It’s back to Las Vegas for now, storage for the bike and a flight back to the east coast for me. This trip has come to an end for now.

- Acadia National Park

- Adirondacks

- Aerial

- Airstream

- Ancient Bristlecone Pines

- Anza-Borrego

- Appalachian Trail

- Arches National Park

- Backpacking

- Bad Larry

- Bears Ears National Monument

- Boatpacking

- Boston

- Bryce Canyon National Park

- Canoeing

- Canyon de Chelly National Park

- Canyoneering

- Canyonlands National Park

- Capitol Reef National Park

- Caribbean

- Catskills

- Cities

- Climbing

- Colorado National Monument

- Colorado Plateau

- Death Valley National Park

- Europe

- Fisher Towers

- Grand Canyon National Park

- Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument

- Grand Teton National Park

- Gunks

- Hiking

- Iceland

- Joshua Tree National Park

- Lassen Volcanic National Park

- Manzanar National Historic Site

- Mojave Desert

- Mojave National Preserve

- Mountaineering

- Mt Washington

- Mt Whitney

- Natural Bridges National Monument

- New York CIty

- Pacific Northwest

- Petrified Forest National Park

- Pinnacles National Monument

- Red Roamer

- Road Trips

- Rocky Mountains

- Ruins

- Sailing

- San Diego

- San Francisco

- Sequoia National Park

- Sierra Nevada

- Skiing

- Sonora Desert

- Spelunking

- Superbloom

- Superstition Mountains

- White Mountains

- Yellowstone National Park

- Yosemite National Park

- Zion National Park